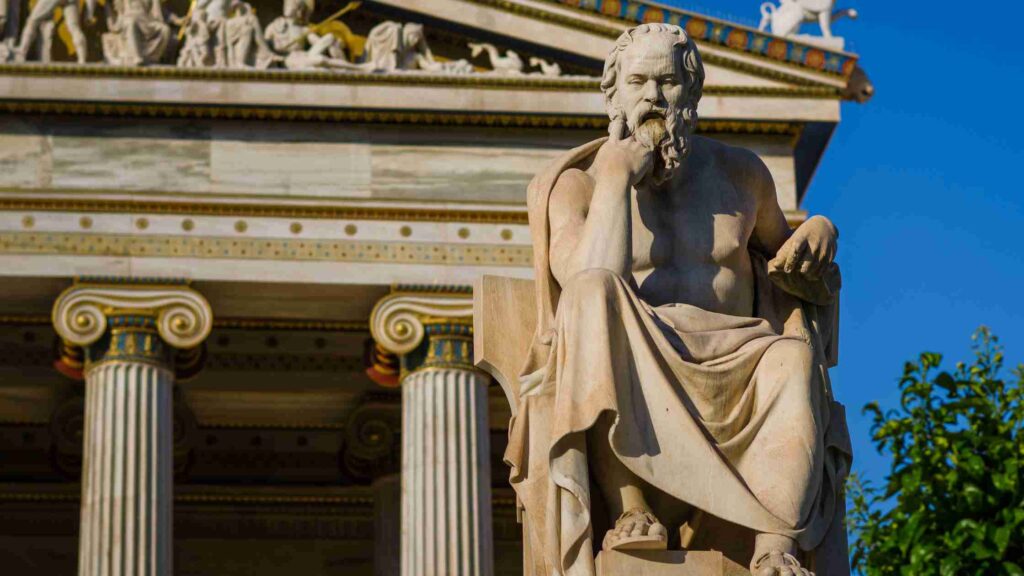

Introduction: Socrates’ Philosophy

Socrates was the center of attention. He had a distinctive appearance: a protruding forehead, a saddlebone nose with an indented bridge, and a broad face. And he was always barefoot.

But his conversational skills were unrivaled. What started as a conversation about everyday examples of masonry work, shoe repair, and horse training soon turned into a discussion of virtues such as piety friendship courage, and the definition of temperance.

He would name household items, scissors, wine bottles, jewelry-and ask where he could get them, and then suddenly ask, “Where do you get a brave and virtuous man?

The Wisdom of Socrates

His words were not long speeches, not long lectures, and of course, he was not paid. He was lucky if he avoided ridicule and assault. His method of dialog was provocative: ask, argue, and test to get people to think.

Some people held grudges because they were rebutted, but some young people enjoyed watching him talk.

Despite the seemingly playful nature of his conversations, Socrates called it “statesmanship” and claimed to be the greatest “statesman” of all.

The great statesmen who ran the Athenian polis, he argued, were great men who did nothing more than “pour out the state and let it fester.”

What drove Socrates to engage in such “strange politics”?

By the time Socrates was born, in 469 BC, Athens was well on its way to becoming a maritime empire.

A decade before his birth, the small Greek city-states had fought a fateful battle against the invasion of the great Persian empire and won.

It was Athens that won the war. With a powerful navy, Athens rallied the city-states around the Aegean Sea to ally in preparation for a Persian re-invasion.

Athenian pride in their identity and culture was sky-high. Athens was “a model for the rest of the world” and “the whole city was a school of Greece”.

But that was as far as it went. The Athenians’ confidence in their democratic identity and supremacy led to their intervention and domination of other nations, much to the resentment of other nations.

The democracy had become an empire and a tyrant.

Exposing the Dangers of Misplaced Confidence

Soon, the inevitable happened. Fifty years after defeating a foreign power, Athens was engulfed in a war with its people.

“The expansion of Athenian power struck fear into the hearts of the rival Spartans, making war inevitable,” wrote the contemporary historian Thucydides.

The entirety of Greece, centered around the two states, was caught in a “trap. Thucydides was particularly interested in the value propagation that resulted from the war.

A time had come when courage was seen as all-purpose, prudence as opportunistic cowardice, moderation as deceit, and prudence as negligence.

The degree of conviction tends to be inversely proportional to the frequency of self-reflection. The more stubborn the conviction, the more it escapes the scope of reflection.

In the process of imperialist expansion and civil war, men destroyed themselves as they destroyed others.

Desires for unnecessary things swelled and then burst, and the basic framework of life crumbled.

In such times, it was Socrates’ “politics” to shake the nation awake from its stupor, drunk with the lust for wealth, power, and fame, and his “statesmanship” to expose the falsity of false certainties.

A life without inquiry is not worth living.

Socrates believed that ignorance is the cause of evil.

Dialogues that ask, probe, and test were the prescription for such ignorance.

Did he believe that humans could arrive at certain knowledge through such testing? Not really.

Socrates did not believe that anyone could arrive at certain knowledge, with unshakable conviction.

What he was asking people to do was to recognize the imperfection of knowledge, not the attainment of certainty.

He called for an examination of certainties based on imperfect knowledge.

Socrates encouraged the examination of certainties based on imperfect knowledge because he judged it to be the way to live as a human being.

“The unexamined life is not worth living.”

Socrates’ teaching is a warning and a call, not just for the citizens of Athens, but for all people.

It is the existential confession of a man who has experienced both the light and darkness of a flourishing life.

Democracy as a “rule of the people” always carries the risk of demagogues.

This is why the ability to discriminate between right and wrong was the most necessary civic virtue to maintain Athenian democracy.

This is no different now that direct democracy has given way to indirect democracy.

In this sense, Karl Popper is right when he says that Socratic criticism is “necessary for democratic life.”

Conclusion

But is criticism and review only necessary in politics?

Humans are constantly faced with new situations and have to make choices.

It’s easy to make choices when you’re confident. The more convinced you are, the less you have to question your choices and the less you have to consider the possibility of other options.

It’s good to be comfortable. But there’s always a risk of bias and blindness with easy convictions and choices.

The only way to deal with these risks is to ask, reason, and test.

Socrates’ dialogues were an example of how we should examine our lives, others, and even ourselves.

In the ruined agora, the chipped, cracked, time-worn stones are real.

Human knowledge and certainties are also shaken and broken, and only those who have withstood the test of time are safe. Unshakable certainty is the most dangerous.